Native Grass Garden

Native Grass GardenWhy Plant Native Grasses?

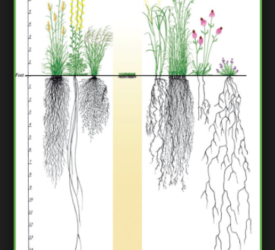

Native grasses are long lived and have little insect and disease problems. They improve the soil and reduce erosion because their root system is extensive. While typical turf grass develops roots within 2-6 inches of soil depth, native grasses exceed eight feet down deep. Once established, they do not need fertilization or water.

In the garden, native grasses provide structure and background foliage to your garden. They also can be focal points, providing winter interest when all other plants are dormant. Because many are bunch grasses (form clumps), they provide cover and nesting locations for wildlife.

What Makes a Grass, well, a Grass?

Names and appearances can be deceiving and confusing. When we think of grass, most think about the typical lawn turf grass. Some plants have grass in the name but are actually forbs (prairie blue eyed grass). Others may look like grasses but really are sedges or rushes. The term ornamental grass is a catch-all term that lumps grasses, sedges, and rushes together.

True grasses are in the family Poaceae. What distinguishes the grasses from other plants is their jointed stems that are usually hollow with a solid joint. The leaves are always two-ranked and alternate (usually flat), composed of a sheaf and a blade with a hinge at their junction. The spikelets all have two-ranked scales (glumes) and florets.

There are two classes of grasses: warm season and cool season. Warm season grasses are bunch grasses (clumps) that grow vigorously during hot summer months. They like hot and dry sites. Seed matures in the fall. Conversely, cool season grasses like it cool with growth during spring and fall; seeds mature late summer. Cool season grasses are found in open woodland or wet to mesic prairies. Native warm-season grasses serve as the essential backbone of prairies and provide food and cover late in the year. Native cool-season grasses fulfill an important role on prairies and other natural communities, by providing forage and seeds early in the growing season.

In our display garden we have eight grasses that are native to Indiana. The table below summarizes the characteristics of each grass.

| Plant | Scientific Name | Height | Warm or Cool Season | Sunlight | Spacing | Flower Season |

| Big bluestem | Andropogon gerardii | 5-8′ | Warm | Full | 2’ | July-August |

| Sideoats grama | Bouteloua curtipendula | 2-3′ | Warm | Full | 1’ | July-August |

| Northern sea oats | Chasmanthium latifolium | 3-4′ | Warm | Full-Partial-Shade | 1’ | July-August |

| Bottlebrush Grass | Elymus hystrix | 2-5′ | Cool | Partial-Shade | 1’ | June-August |

| Switchgrass | Panicum virgatum | 3-6′ | Warm | Full | 2’ | July-August |

| Little bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-3′ | Warm | Full | 1’ | August-September |

| Indiangrass | Sorghastrum nutans | 5-7′ | Warm | Full | 1-2’ | August-September |

| Prairie Dropseed | Sporobolus heterolepis | 2-4′ | Warm | Full | 2’ | July-September |

While grasses dominate the prairie, they are intermixed with many forbs (wildflowers). In this display garden, we have added Lanceleaf coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata), Rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium), Grey-headed coneflower (Ratibida pinnata), Cup plant (Silphium perfoliatum), Dense, Prairie, and Rough blazing stars (Liatris species spicata, pycnostachya, and aspera, respectively), as well as Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa). The grass-forb combination gives a diversity of habitat for native songbirds and insects, adds a splash of color to the summer garden, and provides winter interest when little else is in the garden that time of year.

In the next garden you are planning, consider native grasses. They won’t disappoint and will bring a little prairie to your landscape.

Background

In the 1800’s, European settlers, moving westward from the forested areas of the original eastern states, came into a land covered with grasses and wildflowers. The settlers adopted the French word ‘prairie’ to describe these areas. Historically covering 170 million acres of North America from the Rocky Mountains to east of the Mississippi River and from Saskatchewan, south to Texas, the prairie was the continent’s largest continuous ecosystem. It supported an enormous diversity of plants and animals. The prairie was a harsh environment with intense summer heat, high humidity, harsh winters, and periodic fire. Settlers soon learned that prairie soil was in fact among the most productive soils in the world. What was once millions of acres of prairie in North America has now dwindled to less than one percent, due to agriculture and urbanization.